A Love Letter to The Art Institute of Chicago

I visited the Art Institute of Chicago for the first time in the summer of 2024, and every museum is different, so I walked in not prepared for how I moved I would be seeing certain masterpieces. One of my favorite things about museums is that you’re not chasing beauty. The beauty is already all around you, and you just sort of wander until you bump into the most exquisite pieces that speak to you. Chicago is my favorite city in the country, so I had no doubt that the institute would house fine art that would become some of my favorites of all time.

Monet is one of the first artists I remember learning about as a child, so I was excited to see his work in person, but I was unprepared for the fact that the Institute has 46 artworks by Monet. I spent a good portion of my visit taking each of his artworks in and found that his compelling use of color had a calming effect on me.

What struck me most about this visit wasn’t seeing some of the more famous pieces that one might recognize even if uninterested in art. It was the works I didn’t expect by Black artists whose names deserve to be as universally known.

I discovered Jacob Lawrence’s “The Wedding” in its familiarity and acute detail. A scene so simple as a wedding nearly moved me to tears—maybe for the sacred nature of the setting or because it made me think of my own desire for marriage in a moment I didn’t expect to encounter such a thought.

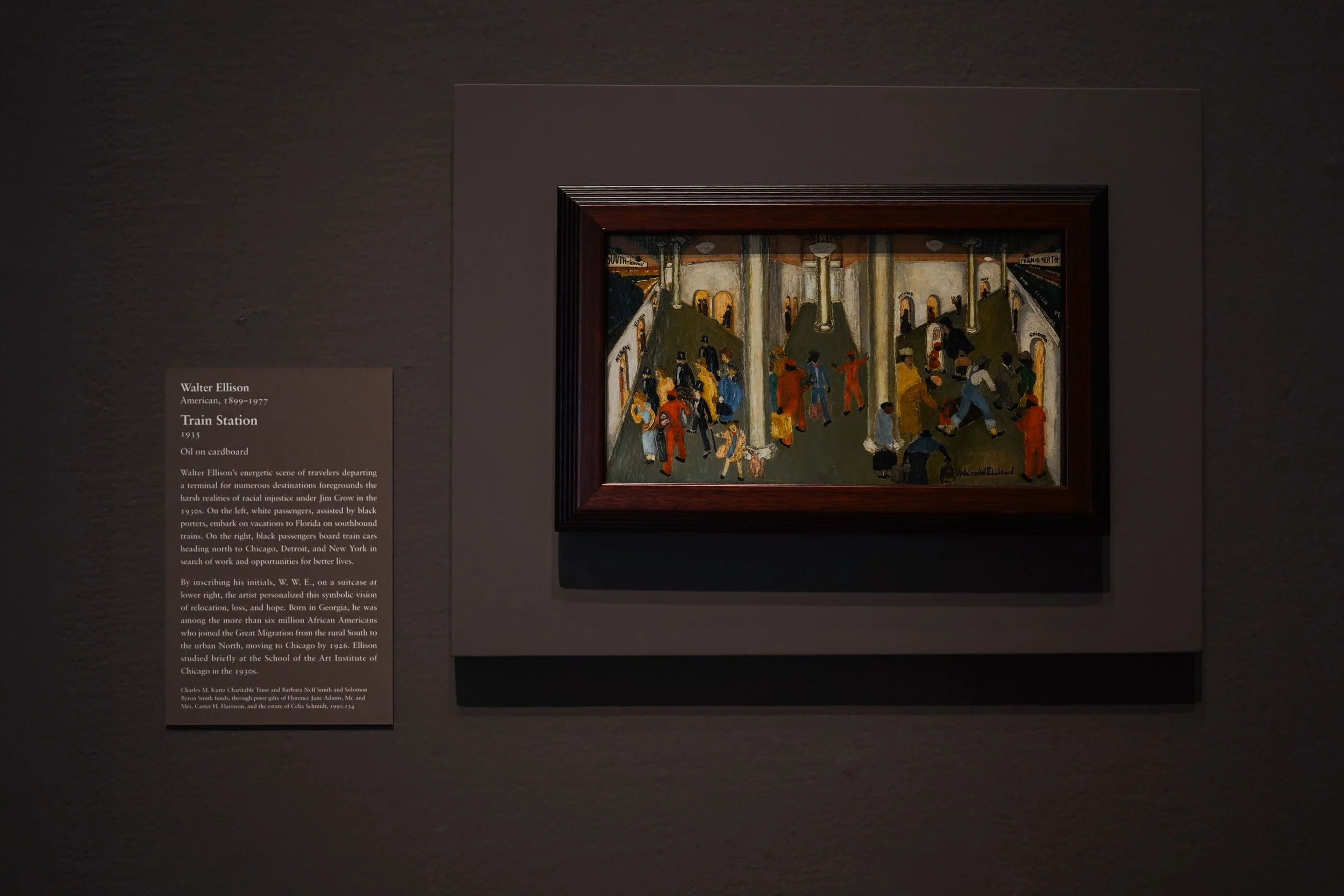

Then there was Walter Ellison’s “Train Station,” a masterclass in movement, color, and maybe most importantly, simplicity. The train station is an every day scene, but there’s a storytelling element to the work that made me wonder where each person was going. It depicts Black life in motion, literally and metaphorically.

I stood in front of both pieces for a long time and have since seen many more Jacob Lawrence pieces, all of which have made me consider what it means for Black people to be seen and depicted so accurately and effortlessly in the narrative of American art.

I tend to love modern art, and like most art lovers, I can spot a Pollock or a Rothko from a mile away. The Institute has several Pollock’s but the one closest to his famously chaotic brilliance is “Greyed Rainbow,” which he painted in 1953. No matter how many times I see one of his artworks, I’m shocked at how his unorthodox technique makes so much sense.

Museums are always so alive with people, and whenever I visit one, I’m particularly aware that I’m around so many people who share a common interest. It’s like attending a concert solo but not feeling alone because there’s a stadium full of people singing the same songs you know and love.

At museums, there are locals who have seen the art many times over but may be having takeaways this year that weren’t apparent to them two years ago. There are art students studying, kids on field trips, and tourists trying their best with an iPhone to capture beauty that simply can’t be captured.

A visit to a place like the Institute has the rhythm of curiosity that I’m always trying to keep pace with. It’s a place to observe art, sure. But it’s also a place to ask questions that you may or may ever receive answers to and that’s what leaves an art lover wanting more.

I’ve heard my brother talk many times about the great work of Edward Hopper, so I have come to recognize his pieces before ever reading a placard. Having done no research on the Institute before visiting, I was unaware I would round a corner to a growing crowd of people gathered around his most famous work “Nighthawks.”

I attended an art high school where one of my earliest assignments was to complete a perspective drawing. To date, that was one of the most difficult assignments and gives me great appreciation for someone who executes perspective so incredibly well. That understanding is what makes me appreciate Hopper’s work even more. It’s not uncommon for lay people to encounter greatness and believe they can execute on the same level with ease, but what seems like a relatively simple undertaking is truly more than meets the eye, and when I look at a work like “Nighthawks,” I’m totally sure no one could have produced this except Edward Hopper.

So, this article is less about telling you to take a visit to the Institute. It’s a love letter that reminds me of the internal and external conversations one might have about art within the walls of a museum and outside of them. This article is a thank you to the Art Institute of Chicago for curating a space where classic and contemporary voices coexist and to the city of Chicago for being the kind of place that lets culture be and breathe.

If you ever find yourself in Chicago, go. And take your time, as you should whenever you find yourself in the presence of art. Let yourself be pulled into the feeling of a piece and dive into enduring conversations between artists across centuries. Don’t be surprised if you leave a little or a lot more in love with art than when you arrived.